By A. Benaissa

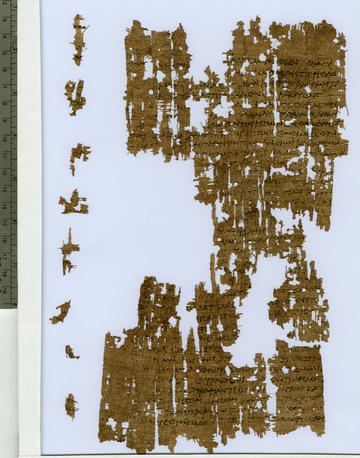

Volume LXXIX of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri (2014) publishes an exceptional papyrus. It preserves a copy of a public inscription in honour of an Alexandrian poet named Apion, recording the privileges and awards conferred on him for his victories in several poetry competitions:

‘Apion, son of Posidonius, from the division of Philopator (in Alexandria), grammarian and scholar, who was the first of men to be twice victor in verse in the Circuit (of sacred games), and thrice won the shield-prize in Argos, and was crowned for a tragedy in Syracuse and at the august contest (in Naples), and took many other crowns, and was the first of poets to have entered (Alexandria) in triumphal procession in a white four-horse chariot: him his native city honoured with public maintenance in the town hall and a golden crown and a gilded crown of the Circuit … [12 lines poorly preserved] … the performers devoted to Dionysus and the other gods (honoured him) with a statue and a portrait tondo in the temple of Dionysus; in Rome the association of sacred victors from the whole inhabited world and their trainers (honoured him) with a statue and a gold-plated portrait tondo … statues of Apion erected(?) in Actium, Olympia, Delphi, the Isthmus, and Nemea; the Syracusans (honoured him) with a public statue and another statue which the people made through individual contributions, and with a gold-plated shield, and with a golden crown (worth) fifty gold pieces, and they presented him with the whole Museum to reside in.’ (Greek text here.)

This can be none other than the infamous Alexandrian intellectual Apion, who flourished in the first half of the first century CE. Apion was a polarizing figure in antiquity. On the one hand, he was prominent as a scholar: he headed the Alexandrian Museum, taught at Rome, and was admired for his erudition and eloquence by a number of later authors. His writings, which have survived only in quotations and paraphrases, span an impressive array of subjects, from Homeric lexicography to gourmet cookery. But as the target of the late first-century writer Josephus, in a defence of Judaism posthumously titled Against Apion, he is also notorious as an opponent of the Alexandrian Jews and an exponent of scurrilous accounts of Jewish history and customs in his Aegyptiaca. Contemporaries criticized his ostentatious self-promotion (the emperor Tiberius dubbed him ‘the cymbal of the world’) and his far-fetched ingenuity.

Strikingly, this is the first time we learn that Apion was also a poet, and one of rock-star status to boot. We know of no Greek poet who achieved similar international éclat in this period. The Circuit (periodos) was the equivalent of a Grand Slam and implied victory at all the great ‘Panhellenic’ sacred games (apart from the Olympics which did not host poetic contests). The theatrical victory in Syracuse—home to a grand theatre surviving to this day—probably coincided with contests organized in the city by the emperor Caligula in 38 CE. Such, however, are the vagaries of tradition and transmission that none of the various ancient writers who mention or engage with Apion refers explicitly to this prominent side of his career, and not a single line of his poetry survives. Thanks to the new papyrus, we can reassess the nature of Apion’s fame and impact in antiquity and ask new questions about the relationship between his scholarly, poetic, and political activities.