Introduction

This is the online version of the exhibition Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts, held in July and August 1998 in the Eric North Room, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, to celebrate a hundred years of publication of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. The exhibition accompanied a three-day conference with papers on the ancient city. The proceedings of the conference have now been published in A. K. Bowman et al., Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts (London 2007). The following pages feature selected images of the published Oxyrhynchus material featured in the exhibition, plus some extras. A few items in the exhibition are not shown here. The accompanying text has been slightly edited and updated where required.

Greek Papyri and Oxyrhynchus

Greek flourished in Egypt for a thousand years. It first began to be widely spoken there when the country was conquered by Alexander the Great, who founded Alexandria in 331 B.C. and then set off to extend his empire in the East. When he died, his governor in Egypt, Ptolemy Soter, established a dynasty of Greek-speaking monarchs, the last of whom was the famous Cleopatra. She joined Mark Antony in his struggle for power in Rome against the man who was to become the first Roman emperor, Augustus. Her fleet was defeated at the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Soon afterwards Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. The Romans made no attempt to introduce Latin in Egypt or any other of their Eastern possessions, which continued to be administered in Greek. Even the Arabs, when they conquered Egypt in A.D. 641, had to carry on the administration for a time in Greek, but within about a hundred years the language had lost its importance and an era of about a thousand years was at an end.

For all this time in every part of the Greek-speaking world books and documents were written on a paper made from the papyrus reed, which was rare outside Egypt, and even there died out in about the tenth century A.D. It is now to be found chiefly in the Sudd, a vast area of swamp in the Sudan covered with thickets of papyrus.

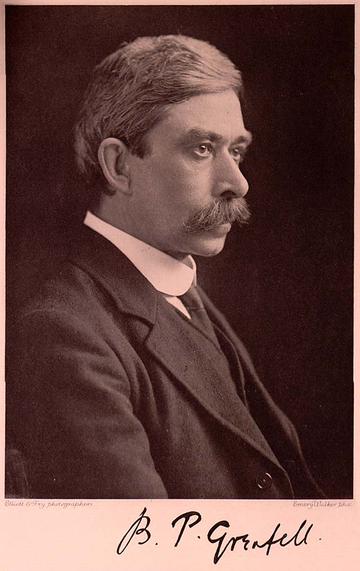

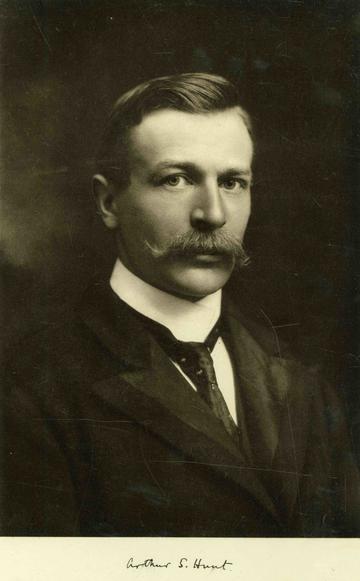

The recovery of papyri began in the middle of the eighteenth century, when the remains of a Greek library on papyrus rolls were found in Italy at Herculaneum, preserved by the debris of an eruption of Vesuvius. By the end of the eighteenth century a few papyri had been discovered in Egypt, the country whose dry climate is most favourable to their survival, and the number slowly grew. By the eighteen-nineties exciting finds of Greek literature, lost works by such authors as Aristotle and Hyperides, encouraged the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society) to commission excavations specifically in search of papyri. In their second season, in 1896/7, B. P. Grenfell and A. S. Hunt, two young Oxford classical scholars, found the site that was to produce the largest collection of all—Oxyrhynchus.

Oxyrhynchus. Its exotic name means ‘sharp-snouted’ and was the Greek for the Nile fish regarded as the incarnation of a god by the original inhabitants. Many other cities in Egypt got their Greek names in the same way—Cynopolis ‘City of Dogs’, Crocodilopolis, and so on. Oxyrhynchus was the chief town of its district and the seat of a local governor. In the Roman period it was a flourishing place with about twenty temples, colonnaded streets, and an open air theatre. When Christianity came, it was famous for the numbers of its monks and nuns. In the fifth century A.D. it had a hippodrome for chariot races and other shows. Almost nothing of all this remains. The stone was carted away for use elsewhere or burnt to produce lime to spread on the fields. A modern village now occupies part of the site. What Grenfell and Hunt found was the rubbish of Oxyrhynchus, which had been carried out and piled into a heap until it became more convenient to start another heap elsewhere, and so on. In the huge rubbish heaps were papyri, sometimes by the basketful, many rotted and fragile, but in such numbers that it took six seasons of excavation to bring them away. 65 volumes with transcripts, translations, and commentaries on the texts have been published so far. Vol. 66 is in preparation. Many more volumes will be needed before all that is interesting has been extracted. Besides the famous literary papyri, there are many documents, some official, illustrating the workings of the Roman and Byzantine Empires in a way that can be revealed by no other sources, and some private, contracts, letters, accounts and lists, which give us valuable glimpses of the everyday business and life of a civilization interestingly different, but not so very different, from our own.

John Rea (1998)

The city took its Greek name from the long-snouted Oxyrhynchus fish (the name means ‘sharp-nosed’), of which there was a local cult in the Egyptian manner.

We are unable to supply an image of the statuette shown in the Ashmolean exhibit, but here is one just as pretty. The fish is shown wearing a crown which associates it with the goddesses Hathor and Isis. The figure of a worshipper kneeling before it suggests that the statuette was a pious votive offering.

Since the start of the Islamic period, the town has been known as el-Bahnasa or Behnesa.

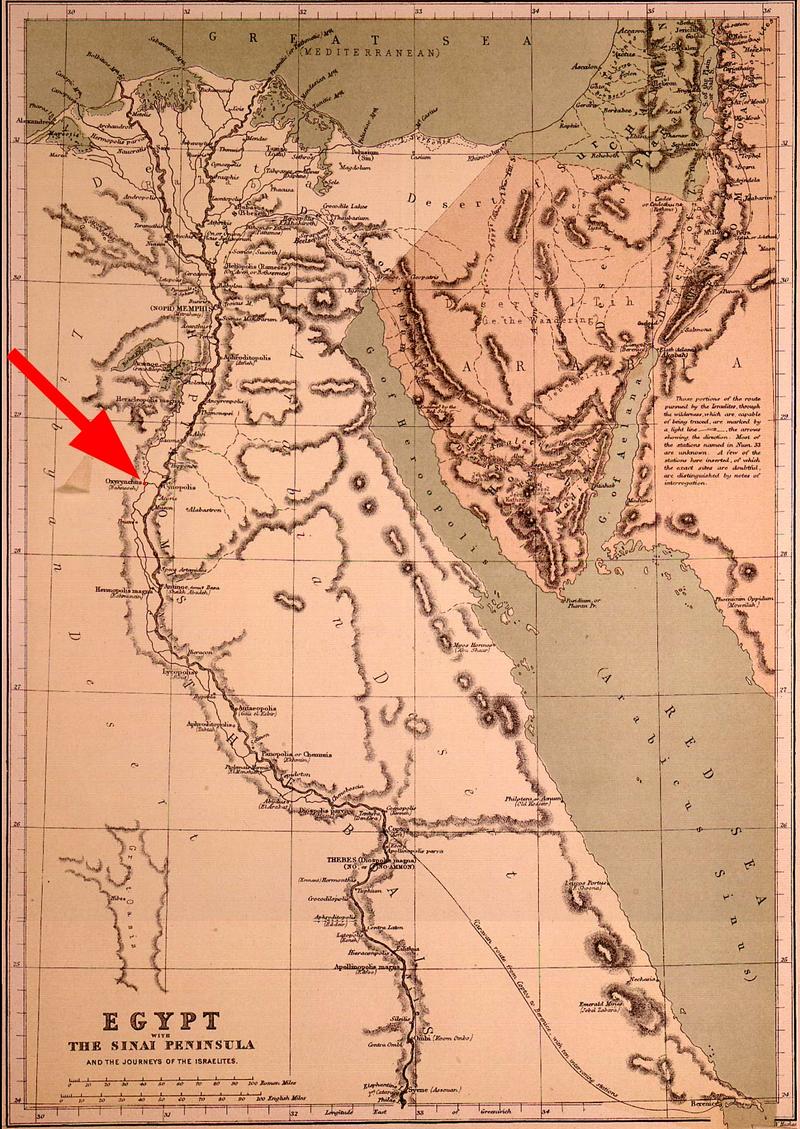

This fine map of Egypt, from Grenfell and Hunt's papers, purports to trace ‘the route pursued by the Israelites, through the wilderness’.

Oxyrhynchus, five days’ journey by road south of Memphis, is marked with a red arrow: at the desert’s edge, and roughly ten miles from the Nile, on the branch of the Nile called Bahr Yussuf. The ancient city’s administrative district lay largely to the north. Its nearest neighbour was Cynopolis, ‘City of Dogs’, named like Oxyrhynchus for its sacred animal.

Plutarch (On Isis and Osiris 380B-C) reports that when the Cynopolitans started catching and eating the sacred Oxyrhynchus fish, the Oxyrhynchites retaliated by eating dog: the two cities went to war, and it took Roman punitive intervention to subdue them. However implausible this may sound, he insists it happened ‘in our own time’.

Bernard Pyne Grenfell (1869–1926)

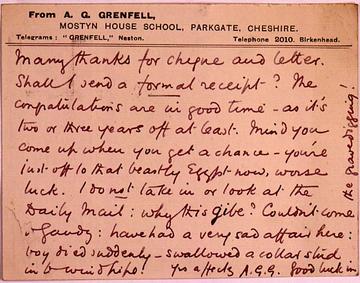

A postcard from Grenfell’s brother survives among the collected ephemera of the Papyrology Rooms:

‘Mind you come up when you get a chance — you’re just off to that beastly Egypt now, worse luck ... yrs affecty A.G.G. Good luck in the gravedigging!’

The tragic incident of the collar stud is a nice period touch.

Grenfell’s cigarettes invoice:

‘14 Mill Street, Conduit Street, London W.

B. P. Grenfell Esq. . . . . . 13th April 1896.

Bought of A. Heronimos, Importer of Turkish Tobacco, and Manufacturer of Turkish and Egyptian Cigarettes:

500 Best Egyptian Cigarettes . . . . £1-7-6

Recv’d with many thanks — A. Heronimos, 13th April 1896’

Grenfell’s taste in cigarettes ensured a useful supply of robust small tins for the safe packing of small fragile objects found on site. A few tins remain in the keeping of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri Project.

Excerpt from A. S. Hunt’s list of requisites for the excavation. The list addressed questions of survival, science, and civilised values: Hunt found room amongst the chemicals for books ('Lucian I & II') and a pillow case.

“2 half pint bottles.

Cartridges. ...

Revolver,

Bottle Ammonia.

Packet Alum. ...”

(full transcript in preparation for publication)

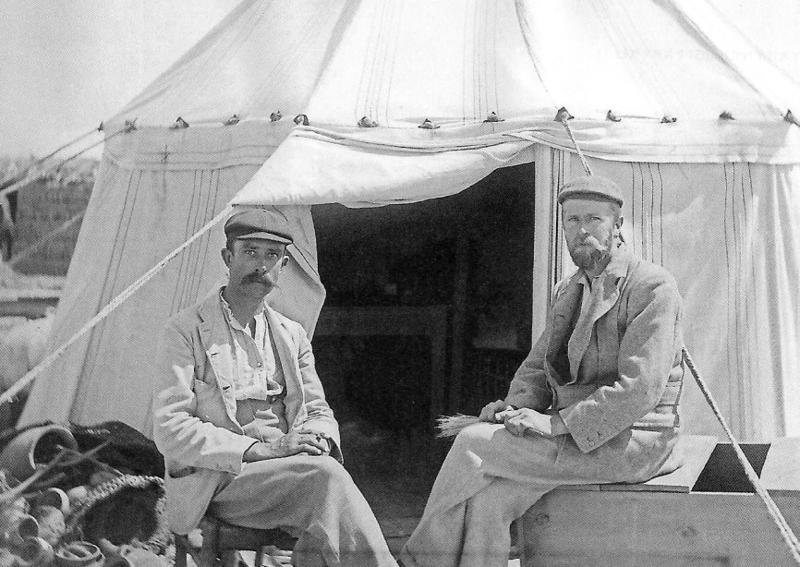

The photograph shows the pair — Hunt on the left, Grenfell on the right — outside their tent at a site thought to be Bacchias in the Fayûm, not Oxyrhynchus where they had a mud-brick house in which to eat, sleep and sort out the day’s finds.

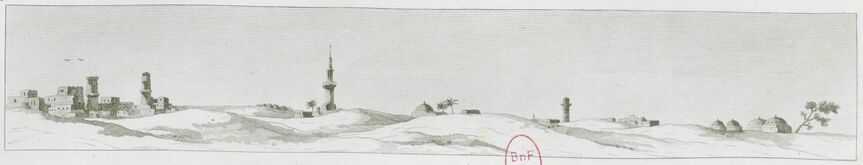

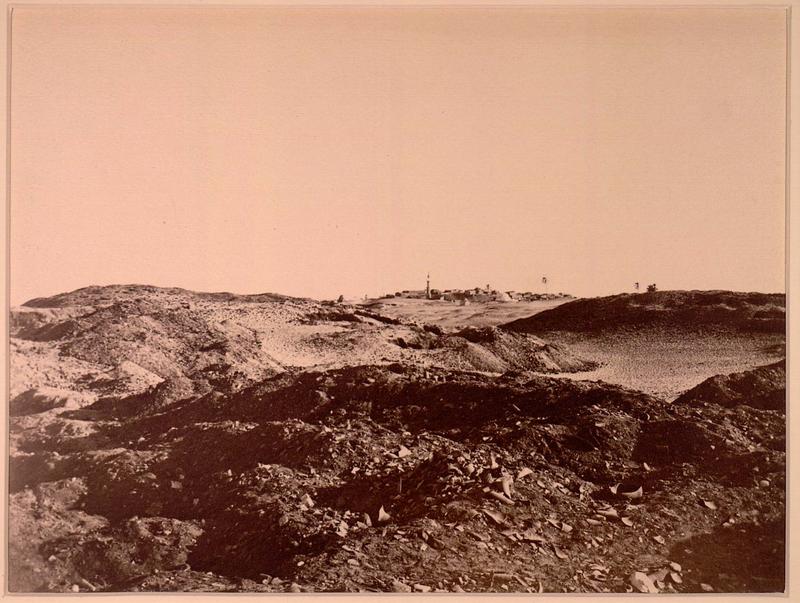

In 1798 Baron Vivant Denon visited the site while in Egypt with the French forces, and made a drawing from out to the north-west of what was by then no more than a village. Some of the architectural details in the distance can be observed more closely in Denon’s second drawing, and can still be observed in modern photographs.

Unwittingly, Denon made his long-distance drawing precisely in the middle of the mounds which would start to yield their papyrus riches to Grenfell and Hunt at the end of the next century, riches which would see their first installment published exactly a century after Denon’s visit.

A view, probably taken by A .S. Hunt during their second season of excavations in 1903, shows the site from much the same angle as the Denon view, little changed after a century, and it confirms the accuracy of Denon’s work, important when considering his other drawing of the site.

The viewpoint is probably from mound no. 17 as numbered on Grenfell and Hunt’s revised site plan, looking between mound 6 on the left and mound 44 on the right. If so, mound 20, ‘Kôm Gamman’, so rich in literary papyri, would be just out of the picture on the right.

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri Project has a modern photograph of much the same view. At this distance, little seems to have changed, and details in Denon’s drawings (see also his sketch of the ‘Phocas Pillar’) can still be observed.

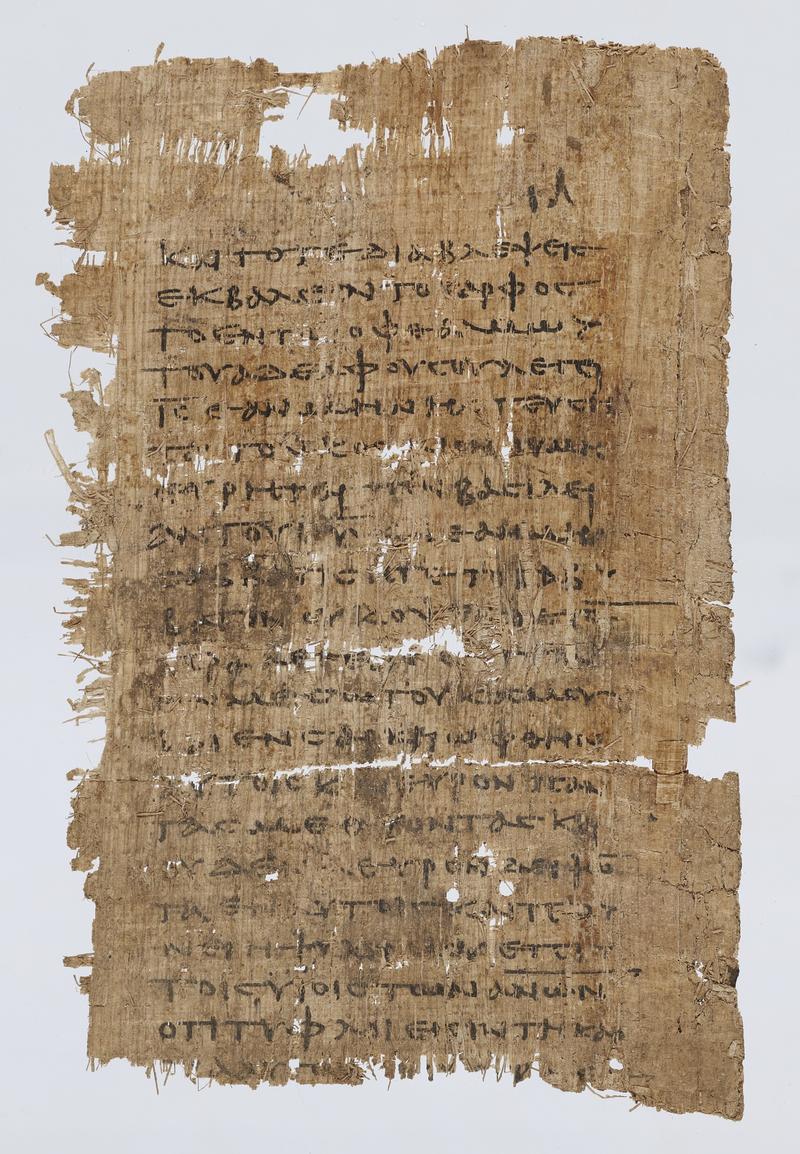

‘Jesus saith, I stood in the midst of the world and in the flesh was I seen of them, and I found all men drunken, and none found I athirst among them, and my soul grieveth over the sons of men, because they are blind in their heart, and see not ...’ — Logion III, lines 11–21.

‘Jesus saith, A prophet is not acceptable in his own country, neither does a physician work cures upon them that know him.’ — Logion VI, lines 9-14.

Grenfell and Hunt found this page from a papyrus book on their second day of digging in the rubbish mounds of Oxyrhynchus, and quickly recognised it as preserving apparently unknown 'Sayings of Jesus' – the fulfilment of a late Victorian dream. This was to be papyrus no. 1 in their first volume, but their enthusiasm led them to publish it in advance in a small booklet, which came out in 1897, the same year that they found the papyrus and a year before the publication of Part I of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

The status and origin of these ‘Sayings of Jesus’ was hotly disputed at the time: Grenfell and Hunt took them to be a collection of sayings, independent of the Four Gospels, and dating from perhaps as early as the first century CE. Later research has identified the text as from the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas, known from a Coptic version.

Oxyrhynchus’ ‘Jesus connection’ doesn’t end there, according to an early mediaeval Arabic epic, the Kitab Futuh al-Bahnasa al Gharra (‘The Conquest of Bahnasa the Blessed’). It tells us that Mary and Joseph stayed at Bahnasa (Oxyrhynchus) when they fled from Judaea to Egypt with the baby Jesus to escape Herod’s persecution. The town became a major Christian centre as a result of this tradition.

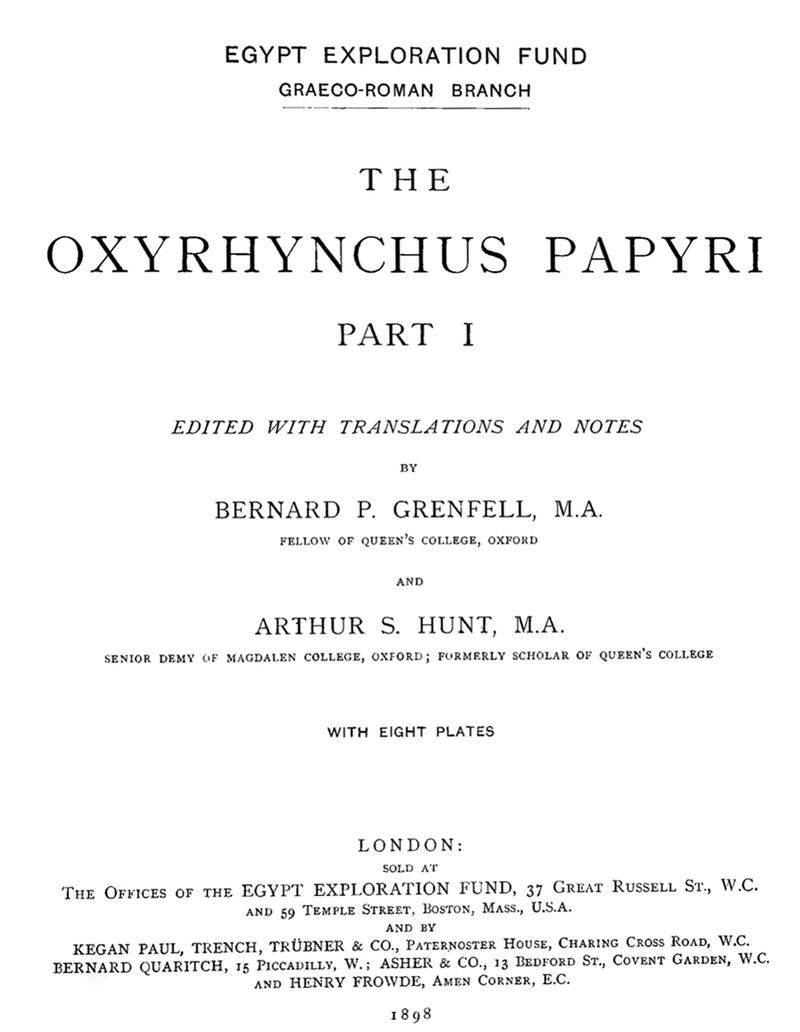

Grenfell and Hunt brought out the first full volume of publication of their finds at Oxyrhynchus with commendable speed in the year after the excavations, not an easy task given the then unfamiliar nature of much of what they had found. They published both literary and non-literary papyri to represent both sides of ‘a collection of papyri ... abounding in novelties of all kinds’. Prize literary items included the Logia papyrus — ‘Sayings of Jesus’, from the second or third century AD, which they had published in a separate pamphlet the year before — and a poem of Sappho, P.Oxy. I 7. ‘It is not very likely that we shall find another poem of Sappho ...’, Grenfell and Hunt wrote. Their pessimism was misplaced.

This was Part I of what was to become the most prolific publication series in the history of papyrology, reaching Vol. LXV in 1998. The books were designated ‘volumes’ rather than ‘parts’ with effect from Vol. XXXIII in 1968, the first to be published under the auspices of the British Academy.

‘The hundred and fifty-eight texts included in this first volume of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri are selected from the twelve or thirteen hundred documents at Oxford in good or fair preservation which up to the present time we have been able to examine, and from the hundred and fifty rolls at the Gizeh Museum.

The bulk of the collection, amounting to about four-fifths of the whole, has not yet been unpacked ...’

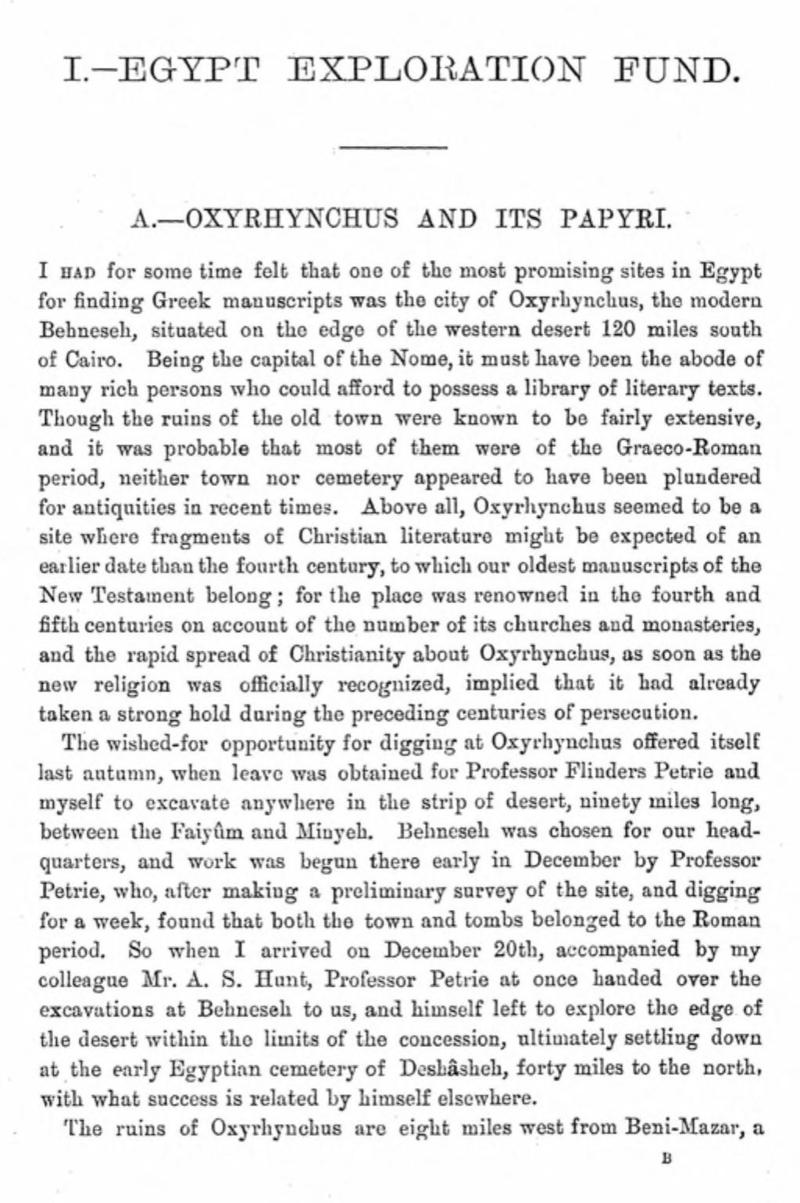

‘I had for some time felt that one of the most promising sites in Egypt for finding Greek manuscripts was the city of Oxyrhynchus ... Above all, Oxyrhynchus seemed to be a site where fragments of Christian literature might be expected of an earlier date than the fourth century, to which our oldest manuscripts of the New Testament belong ...’

Grenfell brought out the report on the first season’s work within months of their return to Oxford; an account in full of over 150 selected items from the season’s finds followed the next year, as Part I of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri.

Grenfell and Hunt left Oxyrhynchus at the end of their first season’s work there in April 1897, and they did not return there until February 1903. A little notebook records their work in that second season appears to be the only survivor of its type. They must have compiled similar notes every season, and the loss of these is particularly to be regretted because a feature of this little book is the packing inventory, which has been vital in understanding the inventory-number system Grenfell and Hunt bequeathed to us and in establishing links between different parts of the collection.